Five(ish) charts that give some context to Venezuelan oil

It has the world's largest reserves, produces comparatively little, and has a type of oil that the US needs.

Update note: On 5th January I updated this article to provide more data on how Venezuela's proved oil reserves have changed over time, and discussion about whether they are too optimistic. I've flagged this additional section with "Update".Over the weekend, the United States bombed Venezuela, and captured its president Nicolás Maduro. There has been a lot of speculation about the legality, true motive and implications going forward.

Oil has been a central part of the discussion. I wanted to get a quick overview of what the global picture looks like. So here are five(ish) simple charts that give some context on the history of oil in Venezuela, and why the United States — which is, by far, the world’s largest producer itself — would care so much.1

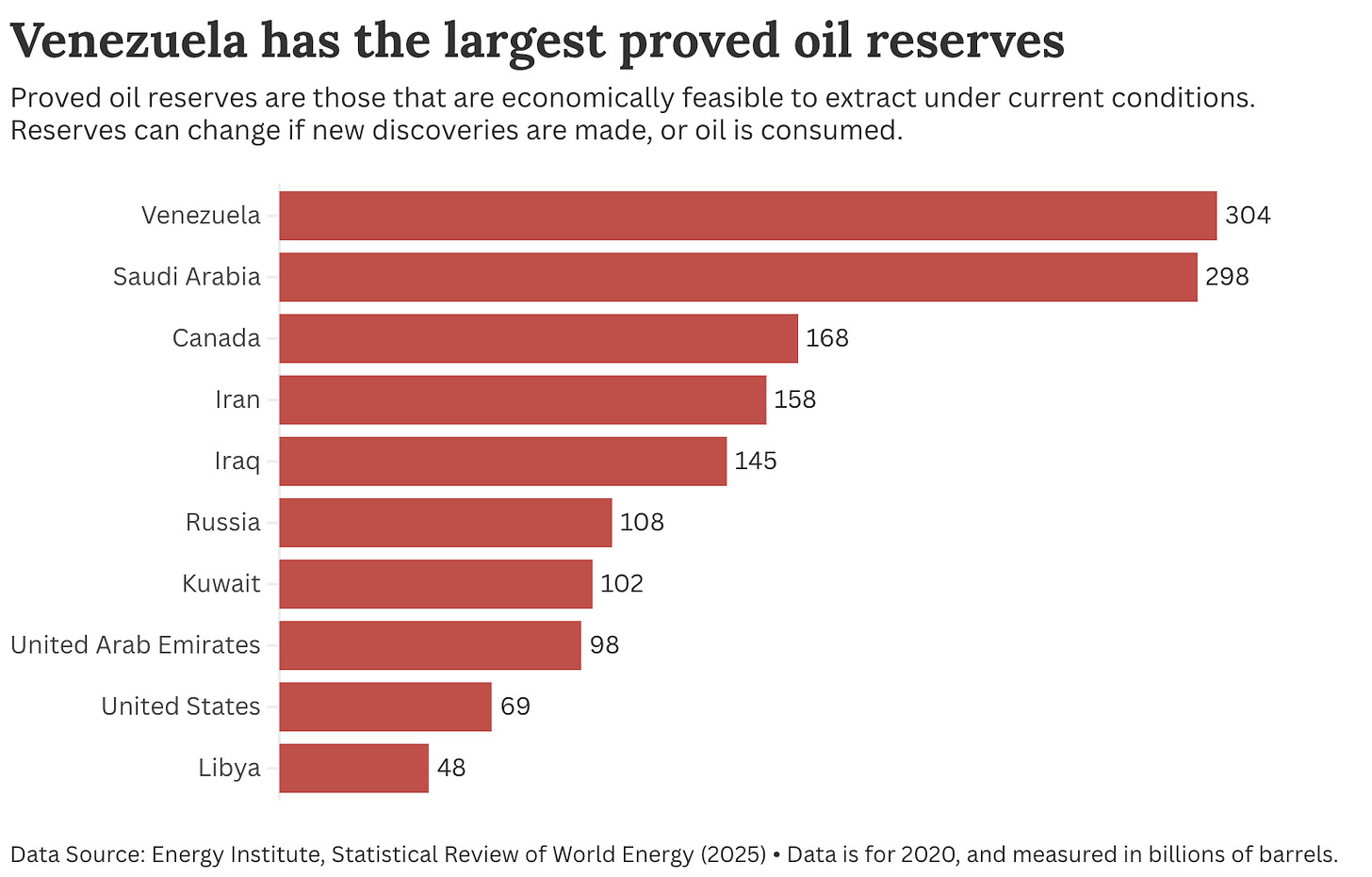

1) Venezuela has the world’s largest oil reserves

While we often think about the Middle East when it comes to large oil stocks, it’s Venezuela that has the largest proved reserves in the world.

The chart below shows the ten countries with the largest proved oil reserves. These are deposits that are deemed economically feasible to extract under current market conditions. This number can change as new reserves are found, or become economic.

Venezuela has about as much oil as Iran and Iraq combined. Its current proved reserves are more than four times larger than the USA’s.2

This data comes from the Energy Institute’s Statistical Review of World Energy.

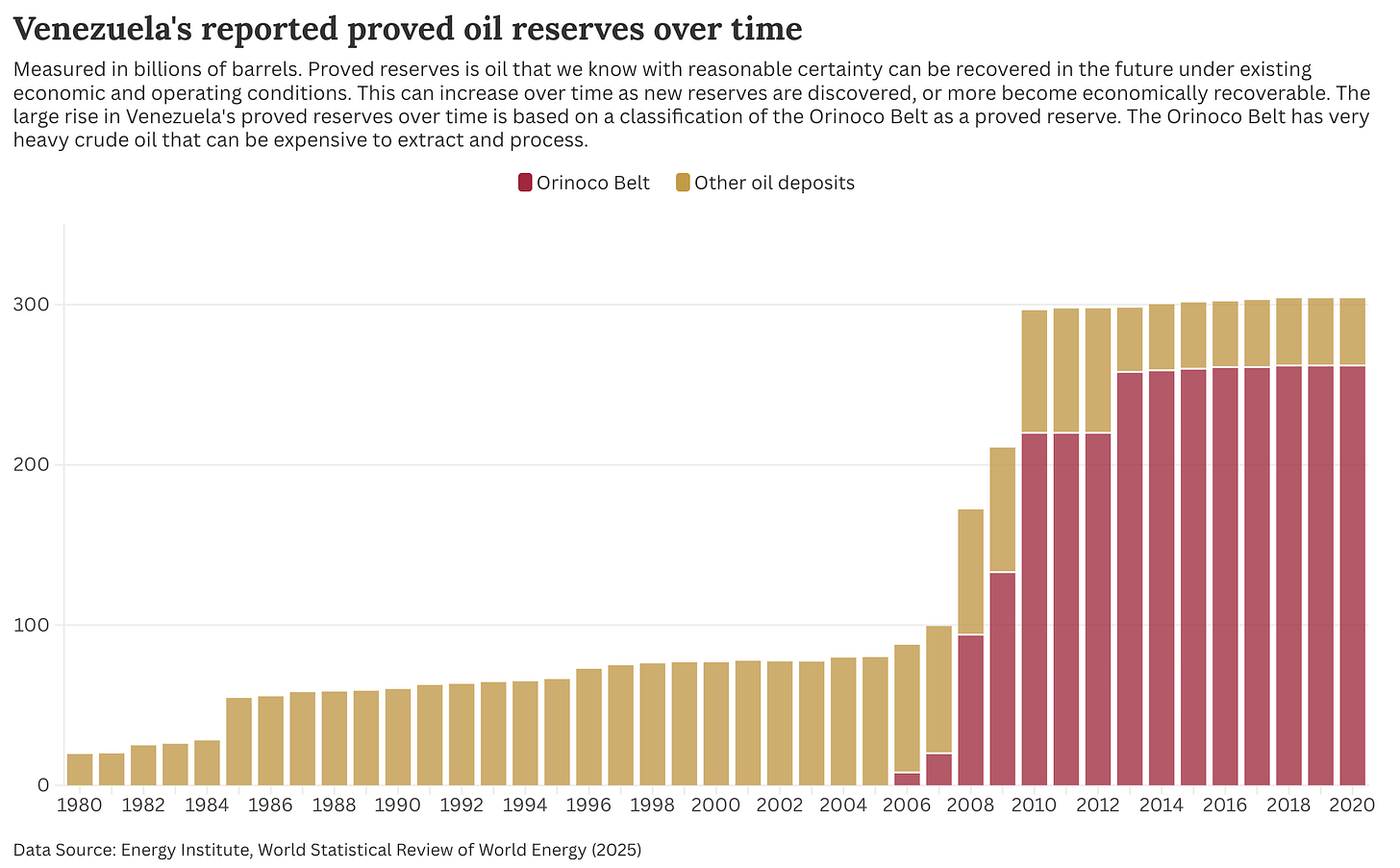

Update: A few people have asked whether these reserve statistics are, in some way, politically manipulated to make Venezuela look far larger than it actually is. This is a valid point, so let’s take a quick look at why there might be concerns about this, and what the implications are.

The charts above — and actually many international datasets on oil reserves — rely on this definition of proved reserves. Again, these are quantities expected to be recoverable from known reservoirs with reasonable certainty under existing economic and operating conditions.

That’s one step up from probable reserves, where there is less certainty/confidence in the technological or economic feasibility.

The argument is that Venezuela’s reported proved reserves were revised upward— using optimistic economic and technical assumptions — because reporting large reserves has a political advantage. This is not an unreasonable assumption, especially when we look at a time-series of how Venezuela’s reported proved reserves have changed over time. This is data from the Energy Institute again.3

The big change happened from around 2007 to 2012, when parts of the Orinoco Belt were classified as proved reserves. The Orinoco Belt does have very large oil deposits. But most of it is “heavy” or even “extra heavy” oil (more on this later) that is often expensive to extract and process. The question, then, is whether this classification is too optimistic, and those reserves can’t really be recovered economically.

Of course, whether it’s economically feasible depends on the oil price. It might be profitable when oil prices are high, but a money-sink when they’re low.

Some analysts suggest far less of Venezuela’s reported reserves would qualify as proved under more conservative price and cost assumptions — closer to around 100 billion barrels. The other two-thirds is then less certain, and perhaps only recoverable when prices are high.

100 billion barrels is still a lot of oil! More than the US’s current proved reserves. But it would relegate Venezuela from being top to being around 7th.

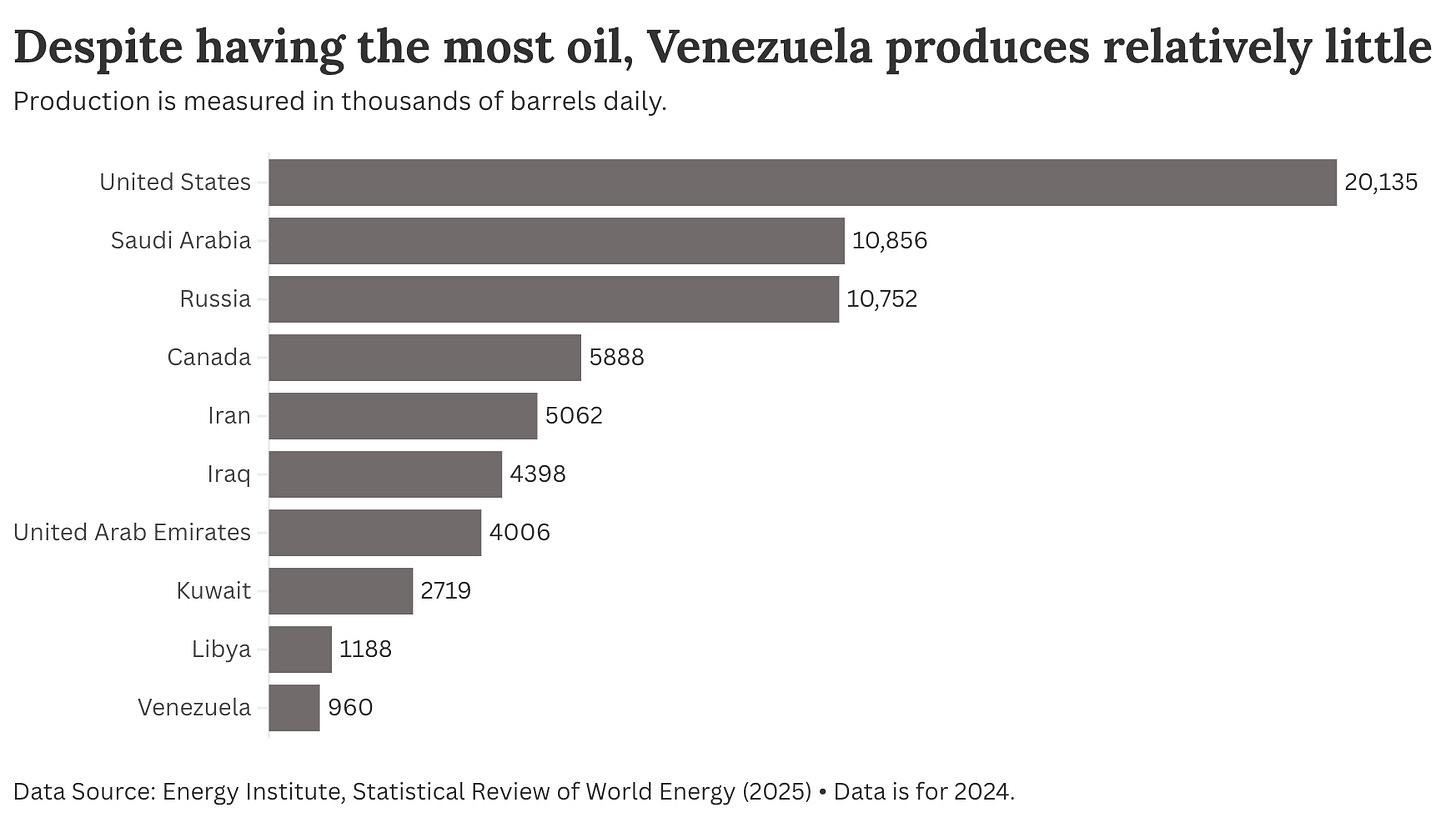

2) Venezuela produces relatively little oil

Despite having a lot of oil, Venezuela doesn’t produce much compared to its own reserves and other large producers.

Here are those same countries (not necessarily the top ten producers, although the US is the world’s largest). Venezuela is bottom of the list. It produces less than 5% of the US’s output, despite having far more available.

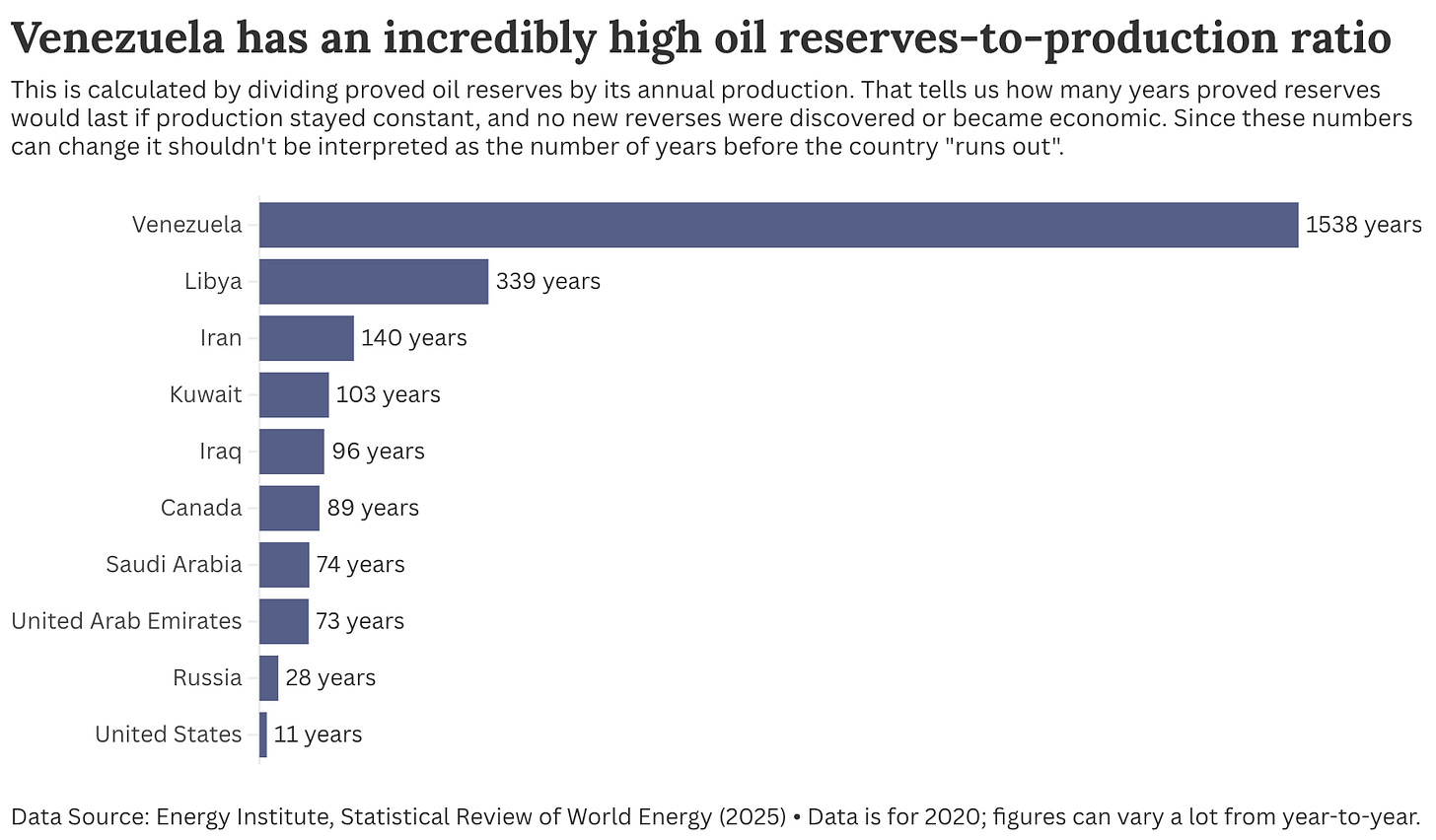

3) Venezuela has an extremely large reserves-to-production ratio

Combining these two metrics gives us the “reserves-to-production ratio” (R/P). It tells us how many years a country’s proved reserves would last if production stayed constant and no new reserves became economically viable. Those are big ifs.

Because reserves and production can change a lot, this is not a prediction of when a country will “run out of oil”.

Since Venezuela has huge proved reserves and produces comparatively little oil, its R/P ratio is very large. In 2020 — a low point for oil production — the Energy Institute had it at over 1500 years. Note that this is based on the 300 billion barrels of proved reserves figure. If we think that’s too optimistic, and only 100 billion barrels are economically viable, it would be 500 years (still a lot!).

This figure is also very sensitive to production: if output were higher, the ratio would fall proportionally (for example, doubling production would halve the R/P ratio). So don’t focus too much on the exact number; the point is that it is big.

That contrasts sharply with the 11 years for the United States. Again, this does not mean the US will run out of oil in 11 years: its proved reserves fluctuate a lot as prices, technology, and investment change.

The contrast is stark: Venezuela has a massive proved reserves base that is not being translated into production, while the US is very active in production and continually replenishes its proved reserves through new drilling and development.

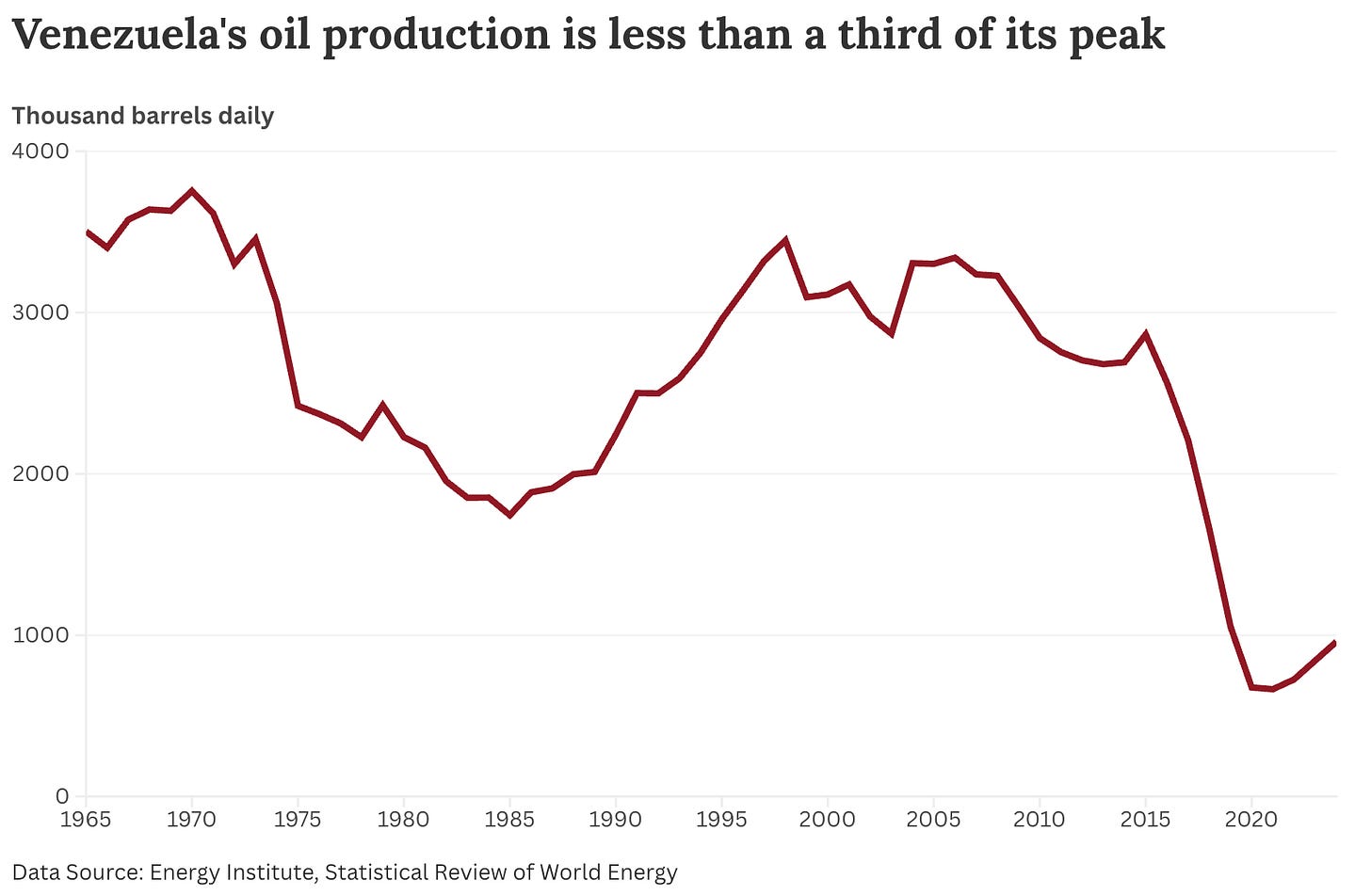

4) Venezuela produces much less oil than it did in the past

Venezuela’s oil production hasn’t always been so low. It was more than three times higher than it is today in the early 1970s, the late 1990s, and the early 2000s. You can see this in the chart.

Venezuela’s output comes from its state-owned oil company’s (PDVSA) operated fields and joint ventures with foreign partners (such as Chevron). In these joint ventures, PDVSA typically owns at least 60%.

Production dropped off rapidly post-2014, when oil prices were very low (which hurt a lot because oil was a large part of the economy). Chronic underinvestment in infrastructure and mismanagement throttled supply. Economic sanctions (including from the US) and limited access to foreign investment throttled export markets and financial support.

Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela’s now-captured President, first came to power in 2013. Most of this recent decline in oil output has largely occurred during his presidency.

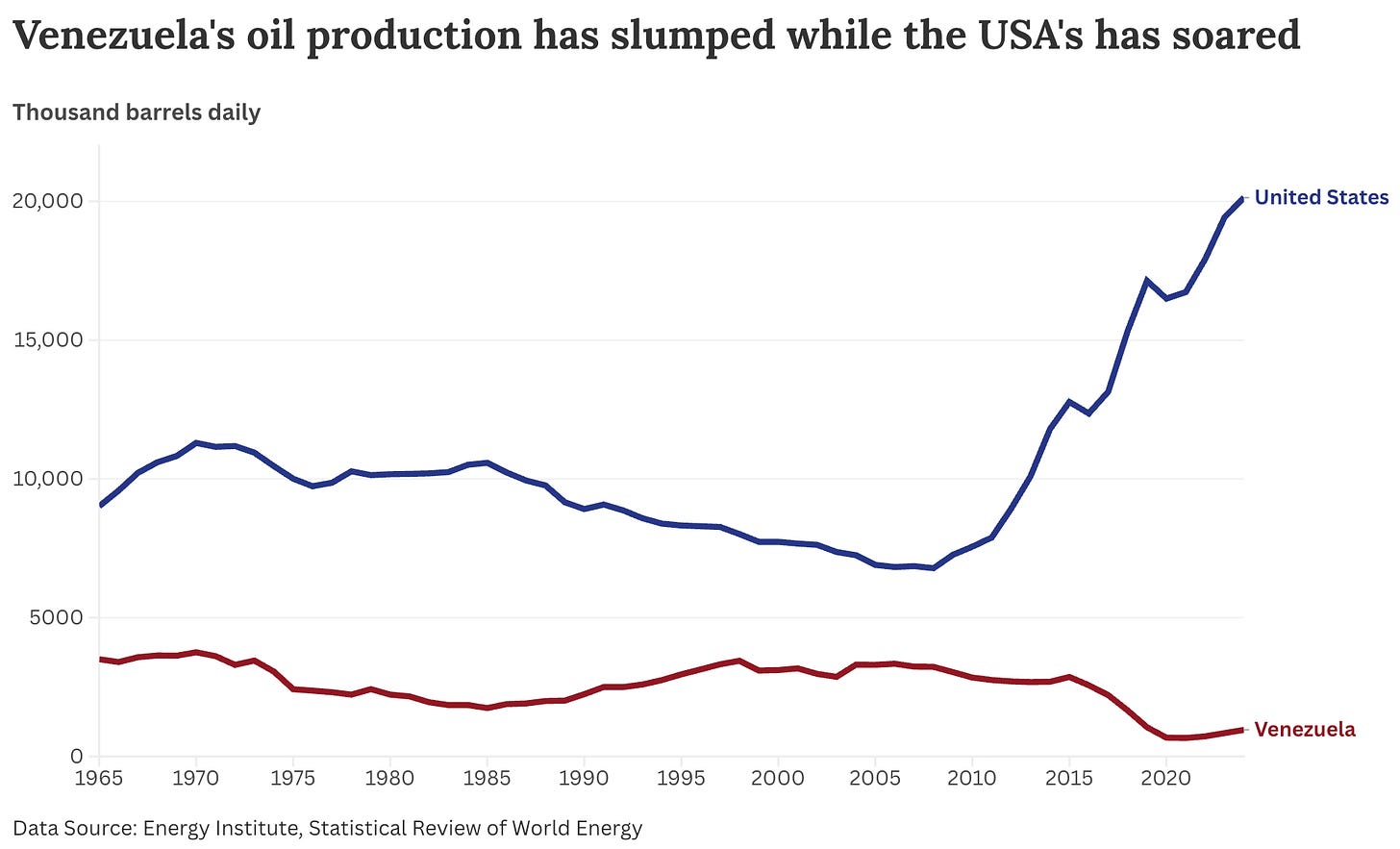

Just for perspective, this is the difference in oil production between Venezuela and the US. While output in Venezuela has declined in the last decade, the US has been at or close to record highs in recent years.

5) Much of US crude oil production is light, while many refineries still rely on heavier crude oil

All oil products are not equal. You can get very different products, and in particular, different densities, ranging from “heavy” oil (which is very viscous) to “light” oil (which is much less so).

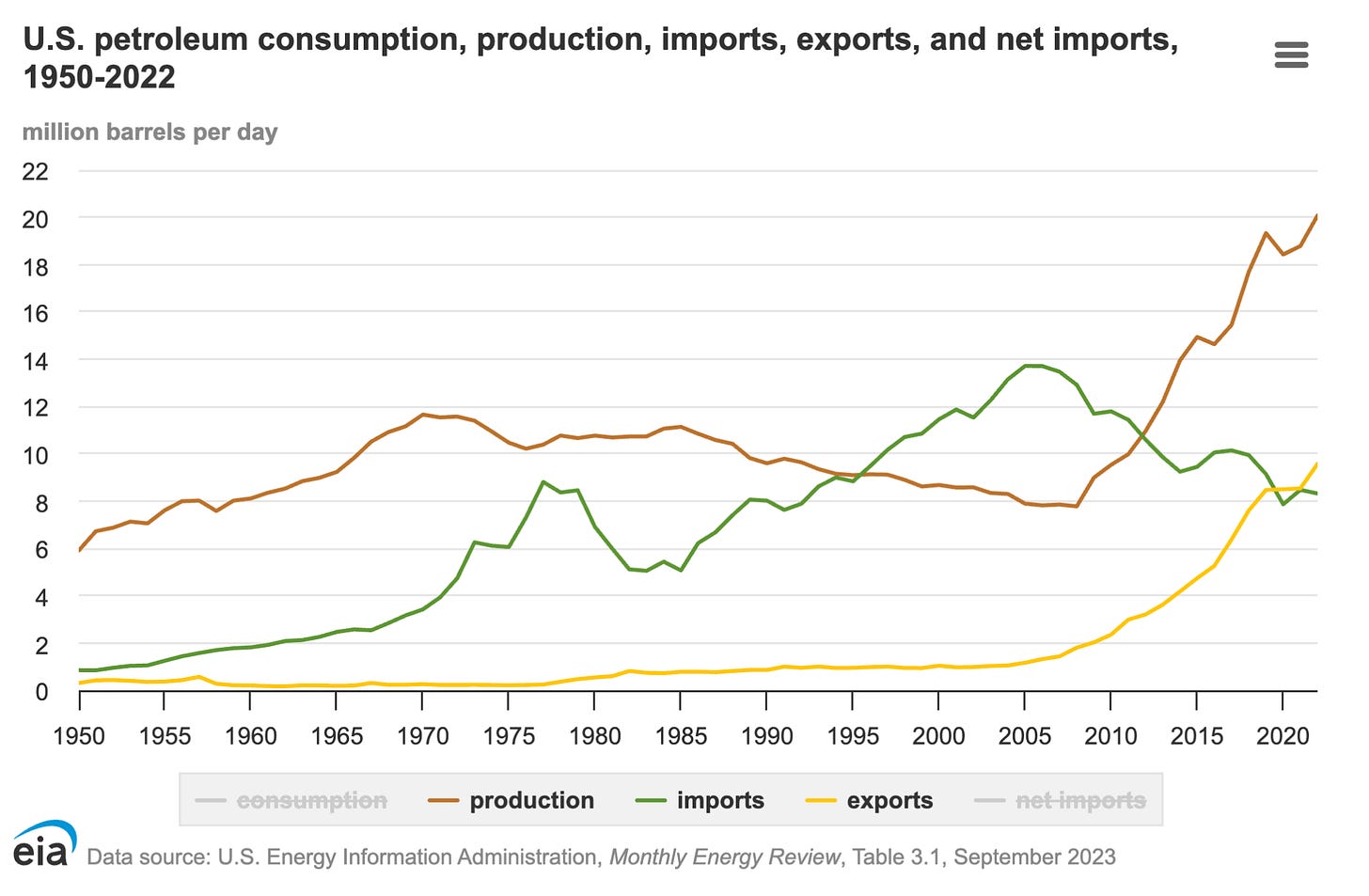

Oil extraction in the US has become increasingly “light”, particularly since the shale revolution (which produces light products). The issue is that many of its refineries are designed to process heavy oil, and it would be expensive to completely retrofit them.

That means the US still imports a lot of oil (mostly heavy oil), despite producing vast amounts domestically. It imports heavy crude oil from countries like Canada and Mexico, and exports lighter crude and refined products. You can see this in the chart below: it produces vast amounts of petroleum domestically, but still exports and imports a lot. This wouldn’t make sense if these were the same products, but they’re quite different.

Where does Venezuela come in? Well, a lot of its oil reserves are the “heavy” kind (or when it comes to the Orinoco Belt, “extra heavy” kind), which the US doesn’t produce a lot of domestically. Venezuela is one potential source of heavy barrels compatible with US refineries.

In summary

Venezuela has the largest proved oil reserves in the world. It has far more than the United States.

A lot of Venezuela’s reported proved reserves are very heavy oils that can be expensive to extract (if they’re economically viable at all). So the exact figure is sensitive to assumptions about the economics of extraction, and the oil price. These are not cheap oil deposits to exploit.

Today, it produces very little. Far less than the United States.

That means it has a large amount of proved reserves that are not being translated into production.

Historically, it produced a lot more, and in principle, could do much more again. However, the timeline for this is uncertain; it could take up to a decade for production to return to previous levels, even with substantial investment.

Venezuela has exactly the type of oil (“heavy oil”) that the US lacks and needs. So its interest is not only about the quantity, but about the type.

Note that here I'm looking at oil purely through the lens of supply, demand and resources.

I'm not looking at the climate implications. To stay anywhere close to global climate targets, most of these reserves will need to stay in the ground.

Again, this is based on proved reserves, and this value for the US can move around a lot from year to year.

In its downloadable data, the Energy Institute has a row specifically for “Venezuela: Orinoco Belt”, which only has data from 2006 onwards. I have assumed that the country’s total minus this Orinoco Belt row is “other deposits”.

Thanks for the great post on quantitative context. There's also an important qualitative element that goes beyond the simple light/heavy crude distinction.

Venezuela's oil production is not just heavy, it is ultra-heavy. Most of those 300 bn barrels of proved reserves (86% of them, according to the Energy Institute) are in a single huge formation called the Orinoco Belt. The oil here is extremely dense (heavier than water), extremely viscous (like pitch or molasses) and extremely dirty (over 5% sulfur and masses of metals like vanadium). The only deposit anything like this size and quality elsewhere in the world is Canada's Athabasca oil sands.

Venezuela and Saudi Arabia appear to have similar proved reserves quantities. In Saudi Arabia, all you have to do to extract the oil is drill a well, and control the resulting flow of oil and gas, which comes bursting out of the ground under its own geological pressure. Let the oil sit in a tank for a short while, and the gases bubble off (and are captured for use as fuels) and the water and sand settle out. The oil is ready to transport by pipeline and ship, and is of a quality readily handled by almost any fuel refinery in the world.

In Venezuela's Orinoco belt, to extract the oil, you have to first pump large amounts of steam into the formation, to melt the hydrocarbons, then use electrical pumps at the surface or in the bottom of the well, up to a kilometer deep, to lift it to the surface. Once there, the "oil" is far too viscous to transport by pipeline or ship, and far too heavy and dirty for most refineries to tackle. So it is diluted by mixing with a much lighter crude oil, or the "condensate" liquids from a gas field, or refined naphtha (a solvent which you can buy as "white spirit" in UK DIY stores). The resulting diluted crude oil (DCO) is exported as Merey blend. This is still one of the heaviest, dirtiest crude oils in the world (16 API, 3.5% sulfur, high acidity and metals content), but it flows just well enough to be transported if kept warm, and some of the world's more complex refineries can handle it, and make transport fuels from it, although usually alongside other lighter crudes.

Venezuela used to produce some lighter, sweeter crudes, which were mostly used as diluents for the Orinoco Belt stuff, but these fields are largely exhausted and Venezuela now needs to import light material to act as diluent to make the DCO.

So while 300 bn barrels of proved oil reserves in the ground may become more politically accessible, they will remain among the hardest and most expensive types of oil to actually produce.

Thanks a lot for this post, Hannah. I never expected to see Venezuelan oil discussed in "By The Numbers", but here we are! You make many good points that are commonly missed in the current discussion about the motives behind the US intervention.

I'd like to add some nuance to point 5, though. It is true that many US refineries (particularly on the Gulf Coast) have significant capacity for processing heavy crude, and that Venezuela was historically a key supplier. However, if you look at EIA data on the capacity of different refining processes in PADD 3 (encompassing the Gulf Coast refineries, data here: https://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/PET_PNP_CAPCHG_DCU_NUS_A.htm), you see that coking capacity (which can be used as a proxy for heavy crude processing capacity) grew a lot from 2000 to 2012 and has remained essentially flat since then. Meanwhile, the actual crude slate processed by these refineries has gotten lighter, with average API gravity rising from around 30° in 2008-2012 to around 34° today.

This suggests that these refineries moved toward building light crude processing infrastructure right when the shale boom took off (while substituting Venezuelan imports with Canadian crude) and did not invest much more into refining heavy crude. Of course, they retain some legacy capacity for it, but there is likely not a lot of idle capacity left.

So while Venezuelan heavy crude is technically compatible with many US refineries, treating it as an unmet need or a binding constraint overstates the case for it. It's one potential source among others that refineries have already adjusted away from over the past 15 years.

Again, really appreciate your data-driven approach to complex topics!