Do subsidies make meat much cheaper?

A little, but not much. Certainly not enough to make them cheaper than meat substitutes.

Last week, Bruce Friedrich, President of The Good Food Institute, published his new book Meat: How the Next Agricultural Revolution Will Transform Humanity’s Favorite Food—and Our Future. If you’re interested in the environmental impacts of our current food system and want to dig into the opportunities for meat-like products without the animals (and their impacts), I really recommend it.

In it, he touches on one question I haven’t seen a particularly good answer to: Do meat and dairy subsidies make them much cheaper?

Bruce thinks the answer is no. It reduces the price a little, but not much. This section in the book was fairly brief, so I thought I’d try to dig in a bit more to see what I could find.

This post is fairly long and dense to get into the details, so here’s the TLDR: Removing subsidies would raise meat prices a little, but only by cents to tens of cents per kilogram. Across the EU, US, and global modelling, removing direct subsidies would likely raise retail meat prices by well under 5%, and often closer to 1% or 2%. This drop would not be enough to change the economics relative to meat substitutes. I should also say that I found it extremely difficult to find a clear answer on this (for reasons I’ll explain), so if you’re hoping for a definitive dollars-per-kilogram figure, apologies in advance.

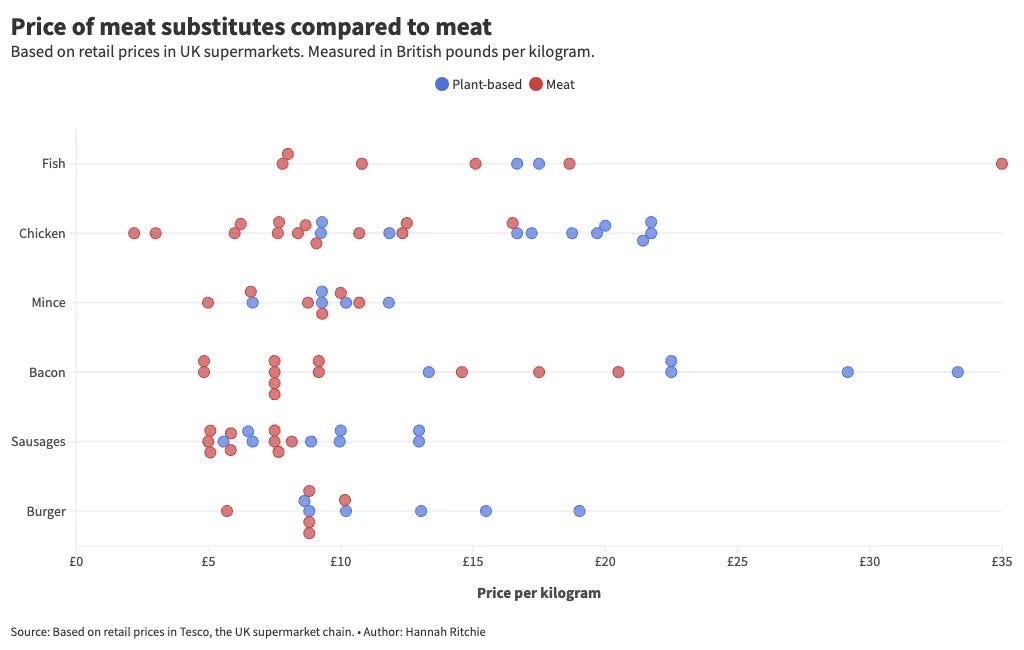

Let’s start with the common argument we’re here to test. As I’ve written about before, meat substitutes tend to be more expensive than their equivalent meat product. Here’s the chart I made a few years ago.

One response to this — and, in fact, the title of my article — is that meat substitutes are too expensive, and need to get cheaper. Another is the opposite: that meat is too cheap. Or, artificially cheap.

That’s where subsidies come in. It’s true that many countries subsidise their meat and dairy industries (as they do for some other agricultural products). This can make animal products cheaper than they would be in a “free” or “fair” market. Consumers might not be paying the true price, but someone is indirectly paying through taxes.

The solution (if you’re in favour of accelerating a transition to more plant-based diets) seems simple then: take the subsidies away and make it a level playing field. Or, better yet, reallocate them to alternative products that have a lower environmental impact.

But how large are these subsidies, and do they really make meat and dairy cheaper?

Direct (explicit) versus indirect (implicit) subsidies

Before we get into the numbers, we need to be clear about definitions and what we’re measuring here.

It’s extremely common to hear large figures quoted like “meat and dairy subsidies are $X billion dollars”. We hear similar statements about fossil fuels, the common one being “Fossil fuels received $7 trillion in subsidies”.

This does not always mean what people think it does. Sometimes people imagine that fossil fuel companies are literally being handed $7 trillion a year. Or meat and dairy farmers get that amount in handouts.

These figures often include several components. There are direct (or explicit) subsidies, which are, in a simplified way, handouts. That either goes to the producers of these products or is used as tax breaks or price cuts for consumers. Then we have indirect (or implicit) subsidies. There are basically negative externalities, such as damage from air pollution and climate change. To be clear: these are real and genuine costs (although we can debate what size those costs are) borne out across society. But they are not handouts.

This chart is from an article I wrote last year, looking at how much subsidies fossil fuels receive. As you can see, explicit subsidies are around $1.3 trillion. The estimated cost of externalities is much larger: $5.7 trillion.

Being clear on this difference is important. I think some people, when they hear “$7 trillion in subsidies”, imagine there is some $7 trillion money pot sitting somewhere that could either be taken away or reallocated to something else. In reality, the pot is “only” around $1 to $1.3 trillion. The other $6 trillion is costs that are dispersed across society, and harder to collect.

It also matters for understanding which levers you would use to reduce these subsidies. Again, you cannot pay for the externalities by pulling subsidies (there is nothing there to pull). The answer would be a carbon tax: charging producers or consumers more to cover the costs of the damage.

What’s true for fossil fuels is also true for meat and dairy. They do create externalities in terms of greenhouse gas emissions, air pollution, land use, and other environmental damages, so there are indirect subsidies (again, we can debate the price). The lever to pull there if you wanted to factor in the “true” cost of these products would be something like a meat tax (or carbon tax if you just wanted to account for climate damages).1

That is not what I’m going to be looking at here. I’m only looking at the direct subsidies farmers and food producers receive. These are the subsidies that a government could, in practice, remove or reallocate, if it wanted to. These are the ones that people would argue “distort” the price difference between meat and meat substitutes.

I can’t cover every country here, so I’ll focus on the US and the European Union (EU) markets, which are often the focus of government subsidies.

How much do subsidies reduce the cost of meat and dairy in the EU and US?

It would be really nice to give a concrete “subsidies reduce beef prices by $X per kilogram” number. Unfortunately, that doesn’t really exist.

That’s because not all subsidies are passed throughout to consumer prices. They can be given as “decoupled payments” to farmers, which are subsidies that are not linked to how much they produce. These are often given to maintain good agricultural land and are therefore reflected in land prices or rents. Since they’re not tied to any marginal unit (X amount per kilogram of meat), these decoupled tend to have almost no impact on shelf prices.

Farmers also receive other payments, though, often in the form of animal feed subsidies or insurance. When crop subsidies are allocated to livestock via animal feed, they account for a large share of the support embodied in animal products. These can reduce consumer prices, but not by as much as the raw numbers suggest. That’s because not all of these subsidies are passed through the production chain. Often, they’re there to keep farmers in business.

Let’s look at some examples.

One of the key recent studies in this area looked at EU subsidies.2 Its Common Agricultural Policy budget — basically payments to farmers — was around €56 billion. It suggested that 80% of this went towards animal products using the authors’ specific accounting approach (so, €45 billion).

Note that this 80% is somewhat disputed as it was based on data from 2013. Another study in this area suggested this was actually more like 50%.3

But let’s go with €45 billion. That’s quite a lot of money. But how much is it per kilogram of meat or milk?

The authors did their own calculations that are far more detailed, but let’s do our own quick sense-check first.

The EU produced 41 million tonnes of meat (of all types) and 140 million tonnes of milk (raw equivalents, before conversion into dairy products) in 2013. So, around 180 million tonnes in total. Divide our €45 billion by this figure, and we get around €0.25 per kilogram of product.

Now, this is very simplified for several reasons: we’ve used raw production rather than retail weights and are assuming subsidies are split evenly across all meat and dairy, which isn’t the case. But it gives us a sense of the magnitude of how these large subsidies break down per kilogram.

In the paper, the authors estimate €1.42 per kilogram of beef, €0.15 for chicken, and €0.28 for pigmeat.4 So our very crude calculation wasn’t that far off!

How much of a difference would this make to their price?

At my local supermarket, a relatively cheap but reasonable quality chicken breast costs around £7 (also €7) per kilogram. A 15-cent discount would cut the cost by around 2%. For bacon, a 28-cent discount might cut the cost by 4%. Beef costs about €14 per kilogram. A €1.42 discount is 10%.

It wouldn’t close the price gap to meat substitutes, though. In my previous analysis, I found the gap for products like chicken was often €3 or €4, not €0.15. The same for bacon or sausages.

But the crucial point is that these are the absolute maximum price impact these subsidies have. It’s probably quite a bit less because only a fraction filters through to consumer prices. Much of it goes towards farmer land rents, inputs or incomes. In reality, that 2% discount might be less than 1%, and the 10% more like a few per cent.

Are things any different in the US? No, if anything, the impact is smaller.

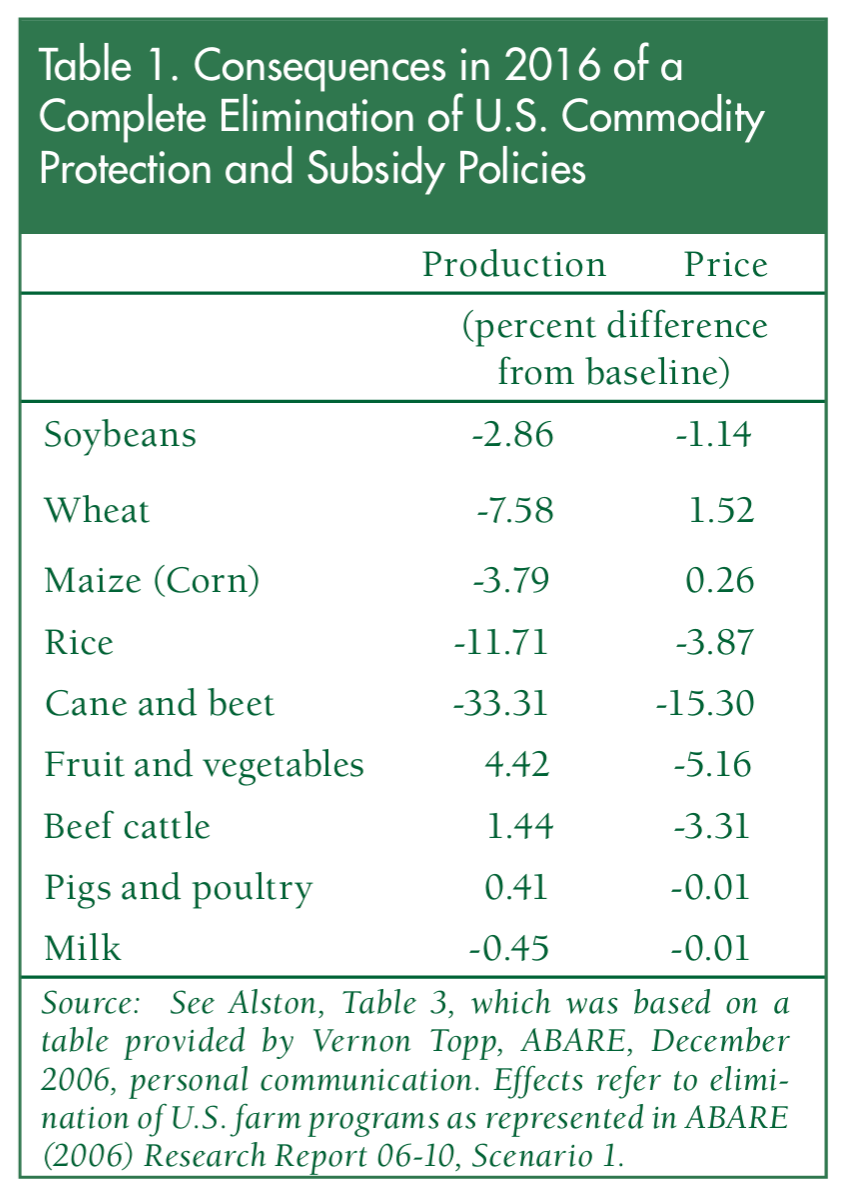

A modelling study suggested that phasing out tariffs and subsidy policies in the US would lower the farm price of beef cattle by about 3.3%, while pig, chicken, and milk prices would fall by far less than 1%.5

Finally, we can broaden this analysis to global markets, drawing on a paper by Springmann and Freund.6 They estimated that, globally, agricultural support measures totalled $233 billion in 2017. Again, not small. Around one-fifth of this was for meat production, and 10% for milk.

They modelled the impact of removing subsidies completely; commodity prices of most meat and dairy products were expected to increase by around 1% to 2%. The largest increase was a 3.5% rise for beef and lamb in OECD countries. Again, not all of that would be passed through to consumer prices.

It’s frustrating to not be able to pinpoint a specific “consumer prices would rise by $ per kilogram” from the research. But my takeaway from this is that, at most, prices would increase by 1% to 2%. We’re talking about cents, or at most, tens of cents of a difference. And this would not come close to closing the price gap with meat substitutes.

Wouldn’t lots of farmers go out of business without subsidies, and that would drive prices up?

One reason subsidies have less impact on consumer prices than we’d expect is that many subsidies are absorbed by farmers as land rents or income support.

But there is, of course, the argument that if these subsidies were removed, some farmers would go out of business, countries would produce less meat and dairy, and prices would increase.

There is some truth to this.

Around three-quarters of all farms (not just meat and dairy ones) would be expected to lose some income if EU subsidies were removed. How many of those would struggle to stay in farming?

I couldn’t find much recent data on this, but surveys from France around a decade ago found that around one-fifth said they would exit farming if all subsidies ended.

Among livestock farmers, smaller-scale beef and dairy farmers would probably take the largest hit to income and margins. Larger, more “efficient” producers of chicken, pigmeat and eggs, less so. In fact, some might be able to absorb some of the production losses elsewhere and see their incomes increase.

Overall, it seems reasonable to assume that production might drop a bit, but not so dramatically that prices surge. Again, we’d be talking about something in the range of a few percent, perhaps up to around 10% for beef.

Another data point to rely on here is New Zealand’s historical experience. It removed all agricultural subsidies in 1984, with many predicting huge drops in production, rural poverty, and farmer exits. But the impacts were far smaller than expected; most farmers found ways to adapt and build sustainable and profitable businesses without financial support. That is only to say that the real-world impact of removing subsidies would likely be lower than pre-policy surveys or expectations, because these often underestimate adaptation and innovation from farmers.

Once again, meat substitutes need to get cheaper

Here are the conclusions I came away with.

First, meat and dairy subsidies are pretty large in aggregate. Tens of billions of dollars every year. You could argue that reallocating these to meat substitutes — relatively immature technologies — could make a big difference to their development.

Second, when we break this down per kilogram, it’s not much. Removing subsidies wouldn’t change prices much. We’re probably talking a maximum of a few percent for most products, maybe slightly more for beef.

Third, this difference falls far short of closing the gap with meat substitutes.

I stick by my conclusion from my previous article: meat substitutes need to get cheaper. I also think this is important if we want to reduce the environmental impacts of food while ensuring people can afford a nutritious diet (and continue to support farmers who put food on our plates). A solution that relies on making food more expensive sacrifices the latter more than I’d want.

In this sense, it’s similar to where I stand on energy. Simply making fossil fuels more expensive without having affordable alternatives just makes energy more expensive, which hits the poorest hardest. That’s why the huge drop in the price of renewables and storage is so crucial to building a more sustainable energy system. You could say the same about food.

It’s at this point that some will argue we already have cheap plant-based protein in the form of beans, peas, and other legumes. That’s true, but people are not really switching to them. Across much of the world, the opposite is happening: people are switching from these plant-based staples to meat and dairy as their incomes rise. That gets to the point of Bruce Friedrich’s book: we have to find a way to meet that demand and want in a way that is better for the environment and animals alike.

Speaking of books, my second one — Clearing the Air — comes out in North America next week (February 17th). Many of you have been asking about it since it came out in the UK. You can now find it here.

Plant-based crops and products also have some environmental impacts, they just tend to be less than that of meat and dairy products. You could argue that they should also be taxed for the negative externalities they generate.

That would raise food prices across the board (although prices of meat and dairy would typically rise more).

Kortleve, A. J., Mogollón, J. M., Harwatt, H., & Behrens, P. (2024). Over 80% of the European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy supports emissions-intensive animal products. Nature food, 5(4), 288-292.

Springmann, M., & Freund, F. (2022). Options for reforming agricultural subsidies from health, climate, and economic perspectives. Nature communications, 13(1), 82.

These costs include subsidies given for animal feed. Those without are typically two to three times lower.

This combines protection policies in the form of tarriffs with subsidy programs, but overall it suggests that these are making little different to prices.

Springmann, M., & Freund, F. (2022). Options for reforming agricultural subsidies from health, climate, and economic perspectives. Nature communications, 13(1), 82.

I agree with you -- it's one of the reasons I've been researching meat taxes more than meat subsidies in my work. While meat taxes aren't very popular, they have more potential to level the playing field more. I also think advocates should focus on, as you mention, increased government subsidies for alternative proteins, like Denmark has.

Here's my post on it: https://morethanmeatstheeye.substack.com/p/meat-taxes-are-super-risky-maybe

Another problem with subsidies that you touch on is that removing them may actually hurt animal welfare. If smaller farms are forced to close, it'll be the big factory farms that stay in business and gobble up that market share, which usually have worse animal welfare practices. In the grand scheme of things, it might not be a big change (since only 1-6% of farmed animals aren't raised in factory farms) but it's still something.

Thanks Hannah, the other and more important side of this is why substitutes for meat are so expensive. I think the answer is the market they cater to. As you rightly point out, one can learn to cook beans and tofu, that will be much cheaper and healthier than meat substitutes. So meat substitutes are by definition not for those willing to pay this premium.

I do think some plant-based products could be made that are easier to cook - just giving-up on trying to resemble meat. Some tofu products in Asia are delicious, cheap, and extremely convenient to cook. Profit margin on that is low, though, so don't expect a western firm to invest anything in that space, shareholders would not allow.