Many people are individually optimistic but think the world is falling apart

Many people feel their own lives are on track, but society is in decline. This can quietly undermine collective progress.

People think the world is getting worse. That’s what almost any survey of opinions across the world would tell you. Things are bad, have been getting worse, and that will continue.

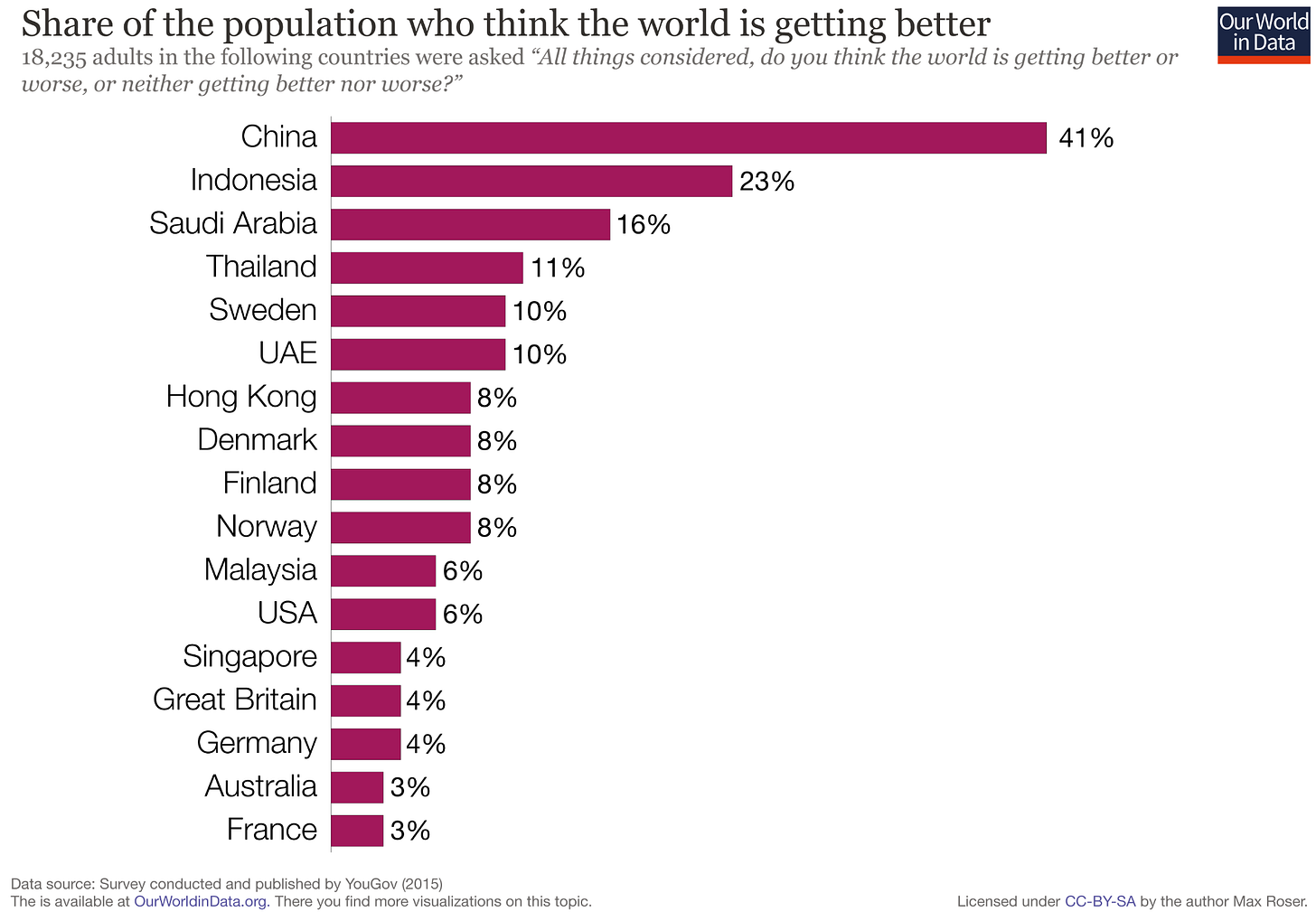

Back in 2015, YouGov asked more than 18,000 adults exactly this question: whether the world was getting better, worse, or neither. Those who thought the world was getting better were in the firm minority. Below, you can see the results across various countries. Overall, rich countries were more pessimistic. This makes sense, as those in low- to middle-income countries have likely seen significant improvements in living standards over the past few decades.

Only a few percent of people in France, Australia, Germany, or Great Britain thought that the world was improving.

If people were pessimistic about the state of the world in 2015, I can only imagine that they are even more so today.1 The post-pandemic world seems gloomier than the pre-2020 one.

People also tend to think that things in their own country are going in the wrong direction. Again, this is most pronounced in richer countries; those at lower incomes tend to be less pessimistic following recent periods of strong economic growth and improved living standards.

But despite their global and national pessimism, most people tend to be optimistic about their own lives. Most say their lives are improving, and believe they will continue to do so.

This perception gap is what I want to explore in this post. This is not an article about whether people are “right” or “wrong” to be optimistic or pessimistic. It’s about the disconnect between how we perceive our own lives and everything happening around us.

Many of us are individually optimistic, but collectively pessimistic

I’m far from the first to highlight this gap. It’s a well-discussed phenomenon: people are often individually or locally optimistic, but collectively pessimistic.2 We have lots of data and research on this on Our World in Data.

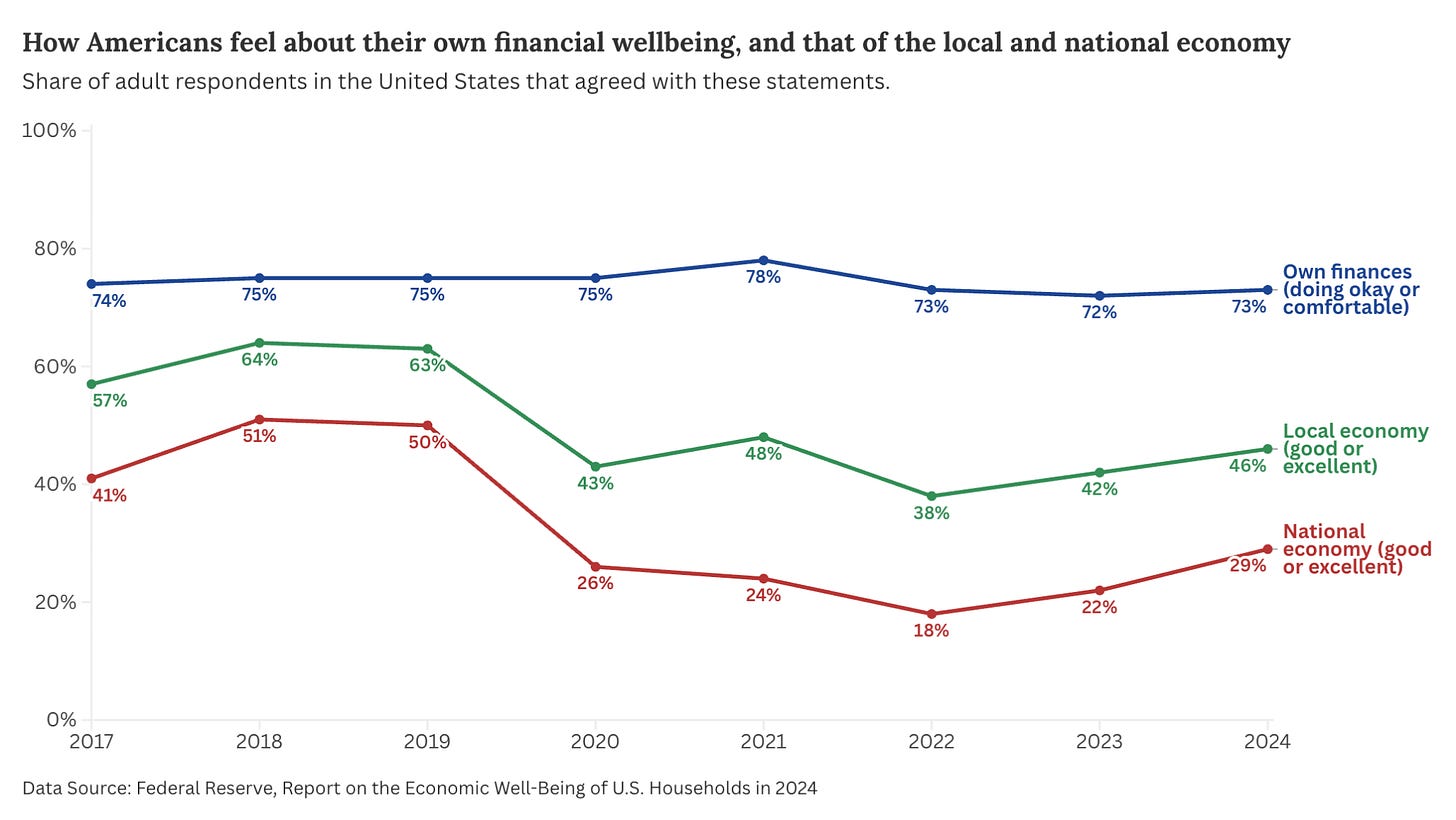

Three years ago, Derek Thompson published an article in The Atlantic titled ‘Everything Is Terrible, but I’m Fine’ on this exact theme. It was primarily focused on the United States, specifically the US economy. Survey data from the Federal Reserve consistently show that people tend to be relatively positive about their own financial well-being, less positive about the local economy, and even less so about the national economy. I’ve updated this chart to 2024, which you can see below.3

But we see this mindset in many different areas.

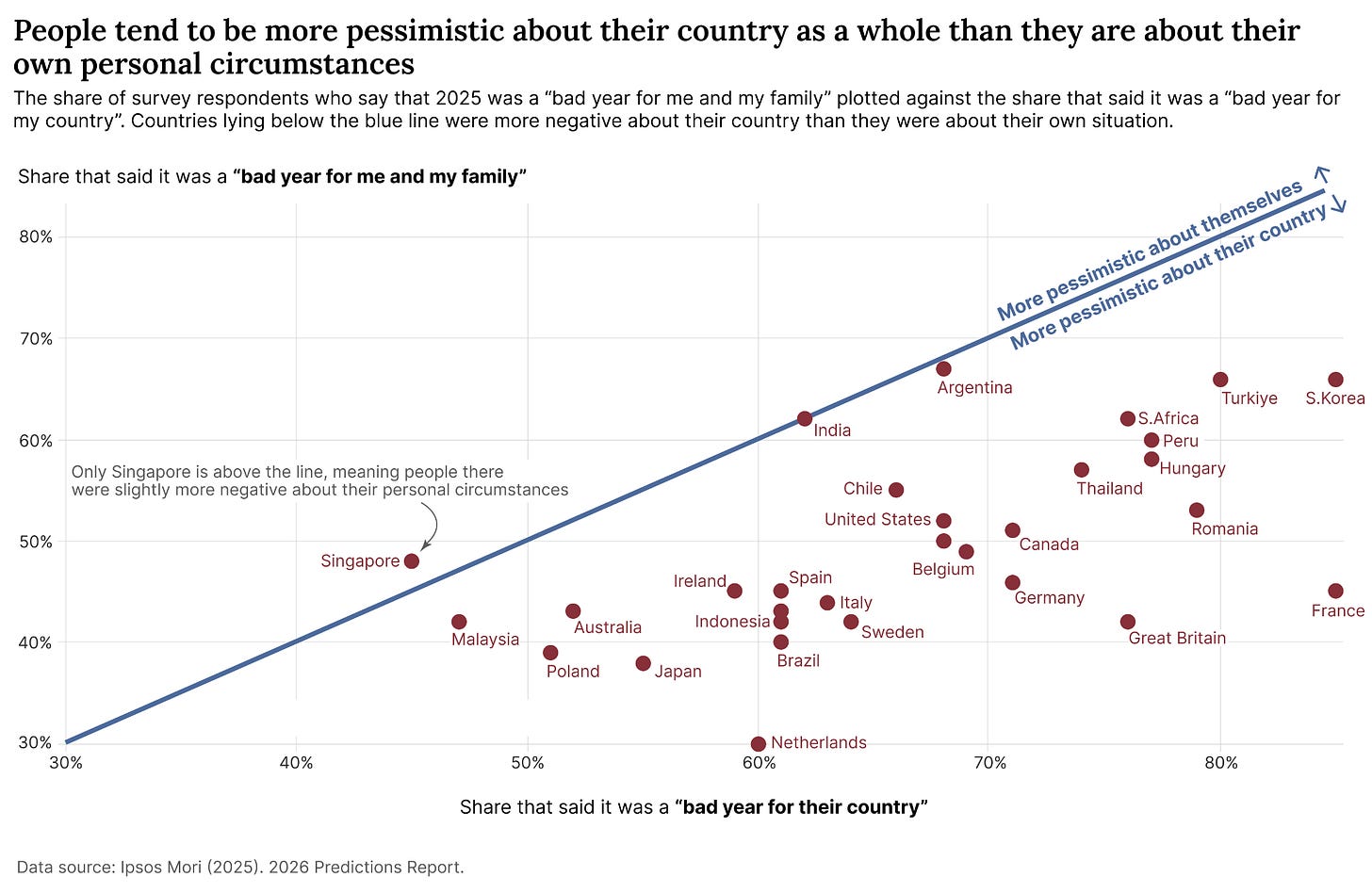

First, on aggregate, very recent survey data from Ipsos Mori show that people are more likely to say that last year was bad for their country than to say it was bad for them and their family. In the chart below, I’ve plotted results from a 30-country survey. On the y-axis, we have the share of people who said 2025 was a “bad year for me and my family”. On the x-axis, the share that said it was a “bad year for my country”.

The blue line represents where these responses would be even; for example, where 60% of people said it was a bad year for them, and 60% said it was bad for their country. Every country, with the exception of Singapore, lies below this line, which means they were more likely to say it was a bad year for the country than they were to say it was bad for them personally.

For example, 85% of the French said it was a bad year for France, but only 45% said it was bad for them. The French were particularly negative compared to other countries. Sixty per cent of the Dutch said it was a bad year for the Netherlands, but only half as many said it was bad for them.

That same survey also suggests that people are also more likely to be personally optimistic about the future than they are to think that the country will start to feel more optimistic. 58% of Brits are optimistic that 2026 will be a better year for them, but only 32% think that Brits overall will start to feel more optimistic about the country’s long-term future. Again, this pattern was consistent across the countries in the sample.

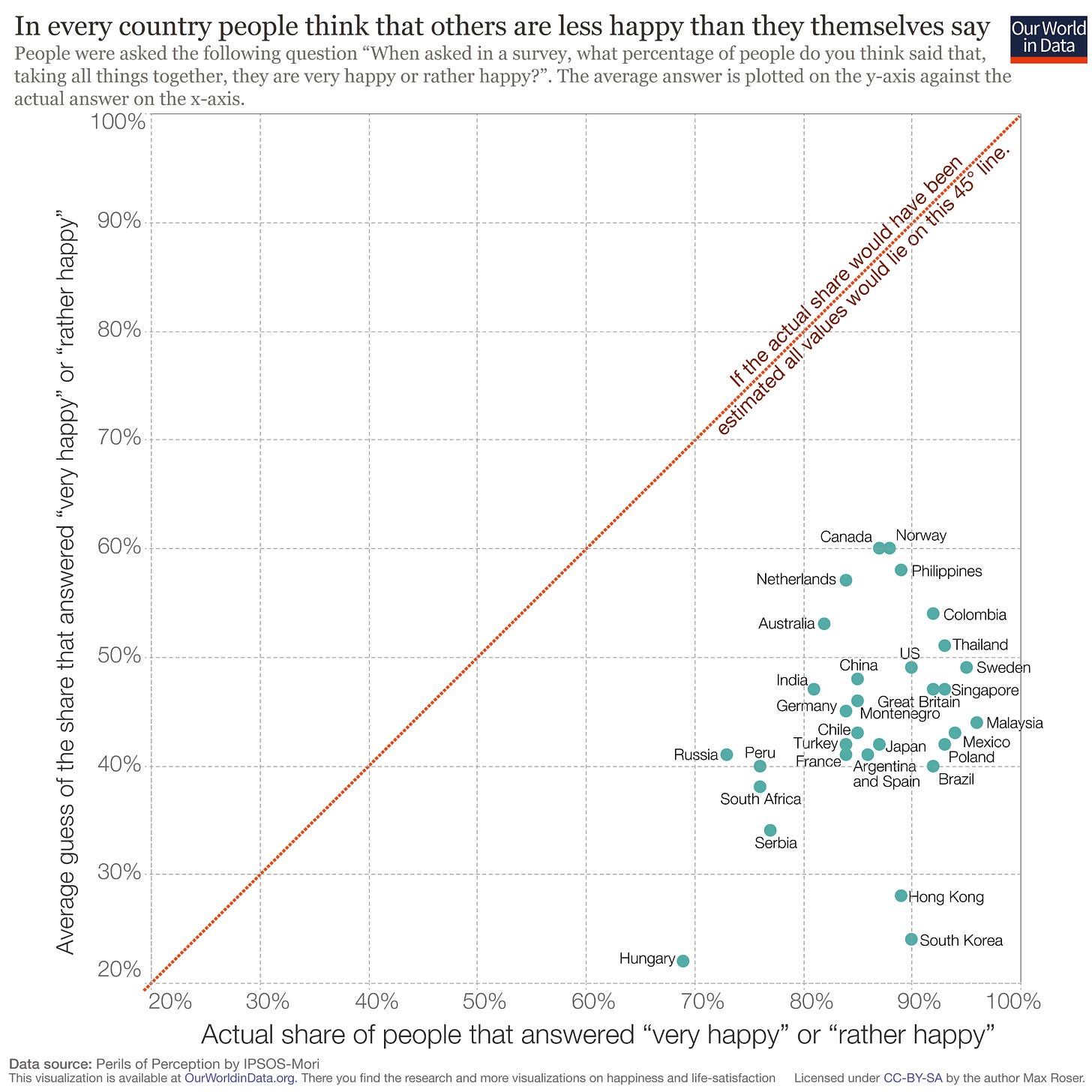

People consistently think that people in their country are less happy than they actually are. On the x-axis of the chart below, we have the share of people in each country who said they were “very happy” or “rather happy”. In most surveyed countries, it was the majority: often over 80% or 90%. On the y-axis, we have the average guess that people made about what share they thought would say they were very or rather happy. These guesses were far lower than reality. In South Korea, for example, people thought that only 25% of their fellow citizens were happy. In reality, 90% were. Since all the countries are below the orange dotted line, people tend to underestimate others’ happiness everywhere.

As I’ve written about extensively, people consistently underestimate how many others in their country “believe” in climate change or support action on it.4 Again, we often think we’re in the minority of those who care about a given issue, but we’re not. We’re simply too pessimistic about others.

In the US, 49% of people say that crime at a national level is extremely or very serious. Just 12% say that crime in their local area is. As Gallup put it: “Americans have consistently seen crime in their local areas as less serious than crime in the country at large.”

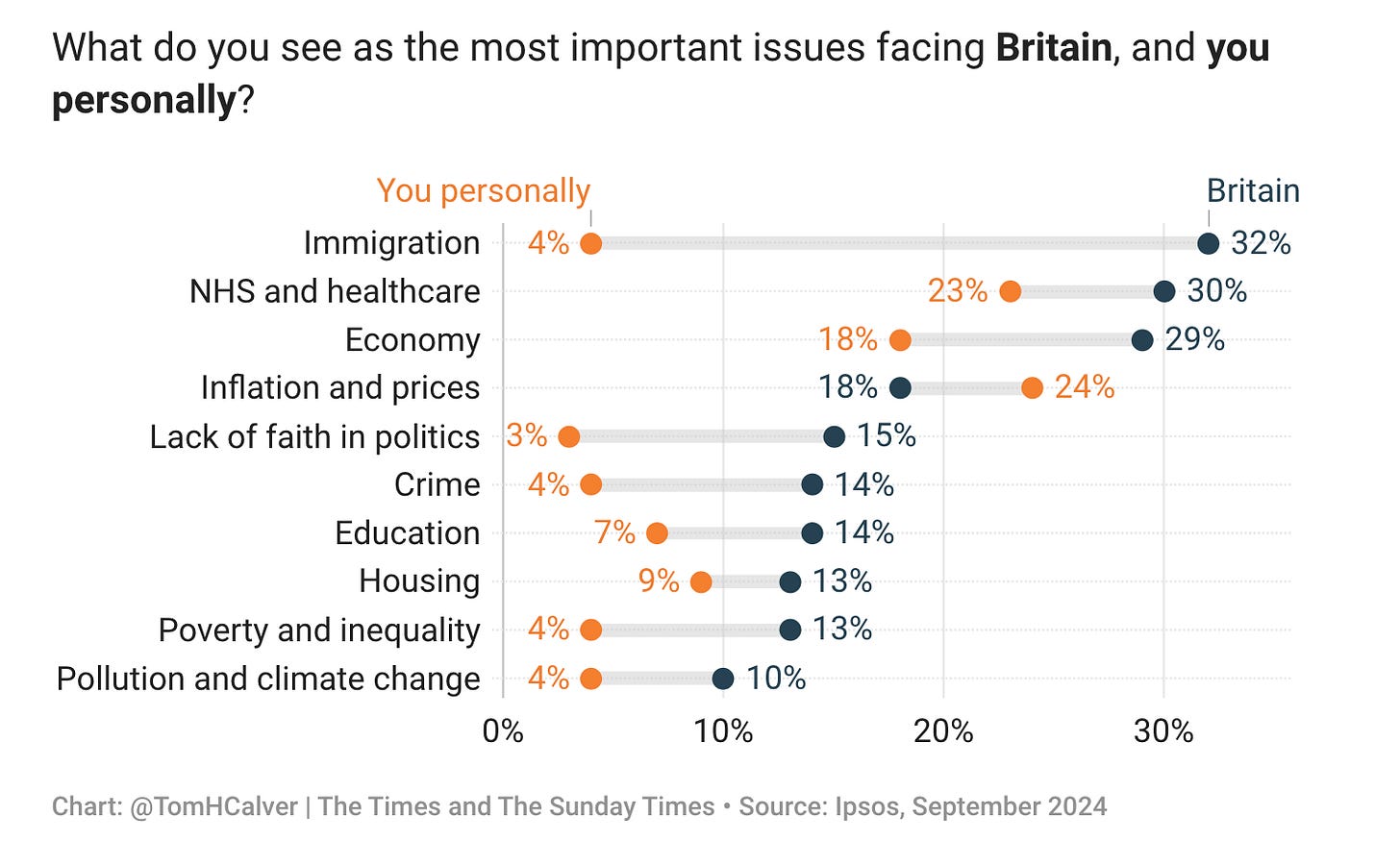

Finally, people are more likely to see problems as collective, not personal: they say an issue affects the country, but not them. As Tom Calver showed in The Times, on almost every issue, Brits were pretty shy about saying it was important to them personally.

32% thought that immigration was an important issue for the country. But just 4% said that it was actually important to them personally. Very few say a lack of faith in politics is one of the most important issues affecting them personally, but a much larger share sees it as one of the biggest issues facing Britain. Crime, education, poverty, and the economy were bigger issues for the country than for them.

Of course, it’s not wrong that some issues affect others, but not us personally. It’s not incoherent for me to say that I’m not directly affected by poverty myself, but can see that it’s a problem for others in my country, or the world as a whole.

But the fact that some of these individual-collective gaps are so large, and almost always consistent (with the exception of inflation), is another nod to the “I’m Okay, But You’re Not Okay” mentality.

Why are we more optimistic about our own lives than other people’s?

There is a range of plausible theories as to why this gap exists.

One is that people are simply too optimistic about their own lives. In other words, they suffer from “optimism bias”. This would partly explain why they are more likely to be positive about their own future; they would overestimate the likelihood of good things happening tomorrow, next month, or next year. It’s less effective at explaining why this gap exists for single-snapshot perceptions, such as rating people’s happiness or their support for action on climate change.

Most theories tend to focus less on why we have a personal optimism bias and instead on why we have a pessimistic social one.

Here, there are a few related ones that make some sense to me.

Theory 1: Our information diet

Imagine a series of nested circles, with you at the centre. Each circle represents one zone removed from us: so, our partner, our family, our circle of friends, our local area, our country, the world.

Think about the “completeness” of information and experiences we have at each level.

We have a pretty complete picture of our own lives. Or, at least, we have a complete story we tell ourselves. We are aware of our history, our challenges, and how we have overcome them. We can see the positives in our lives, the victories. We know about our work, relationships, hobbies, and overall standards of living.

But as we move outwards from there, we have fewer inputs to rely on. We know a great deal about our partner and close family members (although some of those details are private).

We know a bit less about our local area, although we know what it’s like to live there, what the health services and schools are like, the place is clean and looked after, and we have a sense of how safe we feel walking the streets.

At a national level, we rely on small tidbits from people who live in other parts of the country or stories from the national news. What makes it into the national news? Usually bad stuff. The latest horrible murder, political scandal, or disaster. The exceptional, not the everyday, stuff. It’s hard to gauge the lives of tens or hundreds of millions of people, even in our own country, from these drops of stories and headlines alone.

And at a global level, we rely on very little information. Tiny slivers. If we’re basing it on the news, most of what we hear about other countries is negative: it’s a war, a disaster, a threat from one world leader to another. The rest is in darkness. How many of us can really say much about life in Kazakhstan, Peru, China, or [insert almost any country here]?

Most of what we’re hearing about the world as a whole is negative. That’s because bad things happen quickly (and that makes them headline-worthy), whereas good things happen slowly. We’re not hearing about reductions in child mortality, improvements in healthcare or schooling from the other side of the world. Of course, one way to overcome this is to look at statistics, but most people do not.

When someone is asked to reflect on their own life, they draw on a wide range of experiences. When people are asked about “the world”, they recall a very small number of recent events (the availability bias). Those events are likely to be negative, hence they give a pessimistic answer.

Theory 2: Agency and control

The same circle framework can be applied to our sense of agency.

Agency is often crucial to how people feel about the state of things: if they feel like they have some sense that they can do something to change it, they tend to feel more positive that it can be changed.

We have the most agency about our own life outcomes (or, again, perhaps the illusion that we have a lot of agency…this is not the place for a discussion about free will). If things are going poorly, it’s within our control to bounce back (and we often have previous experiences to show that we can).

People often think they have some agency over outcomes in our local area, but much less at a national level. In a recent Ipsos survey in the UK, 72% disagreed with the statement “I can influence decisions affecting the UK as a whole”. Only 56% disagreed that they “can influence decisions affecting my local area”.

At a global level, people feel absolutely helpless. They feel like they have no control over what happens to the world at all.

If we think everything is falling apart, we’re less motivated to improve it

Why does this collective pessimism matter? Again, I’ll try my best not to interrogate whether people are correct in their optimism or pessimism.5 But I do believe that deep-seated, blanket fatalism (which is stronger than pessimism) about our countries, systems and world is unhelpful if we want to improve things.

If we think our institutions can’t be saved, we become susceptible to grand promises from those outside of those institutions. We become less cooperative and trusting of others. Social cohesion breaks down.

If we think our health systems are corrupt and crumbling, then we become sceptical of public health advice. Some might question whether they should vaccinate their kids. If we think foreign aid is wasted money that improves nothing, it’s much easier politically for it to be taken away (with a tragic cost for the millions of lives it saves each year). We become less generous in our own personal giving.

If we think no one else cares about climate change, we stay quiet about it. We don’t expect or advocate for more action.

When we think everything is falling apart — and that’s the common narrative — we struggle to prioritise the areas that need the most attention. Failure to acknowledge where things are going well means we can’t learn lessons about what works and what doesn’t.

It comes back to agency. If we think that nothing can be done to improve things, we’re unlikely to try. This is one reason why I try to emphasise that there are things that each of us can do to make the world a better place. We don’t have to just sit on our hands. Without a sense of agency, we can become cynical and fatalistic that anything can change.

I struggled to find more recent survey data on this exact question. If you know of good cross-country data, please let me know.

In his 2018 book — I'm Fine, But We're Not Doing Well — the sociologist, Paul Schnabel, looked at decades of opinion data from the Netherlands. He found that people were consistently happy with their own personal lives, but always thought that their country was doing poorly.

This comparison is not perfect because the categorisations for personal finances are based on “doing okay” or “living comfortably” while the local and national economy data is based on them being “good or excellent”.

These categorisations probably mean slightly different things to people.

Andre, P., Boneva, T., Chopra, F., & Falk, A. (2024). Globally representative evidence on the actual and perceived support for climate action. Nature Climate Change, 1-7.

Sparkman, G., Geiger, N., & Weber, E. U. (2022). Americans experience a false social reality by underestimating popular climate policy support by nearly half. Nature Communications, 13(1), 4779.

There is survey data that shows a correlation between someone’s awareness of global progress in the past, and their optimism that things can improve in the future. People were asked fairly basic questions about global development; whether extreme poverty was rising or falling, the same for child mortality etc. They were then asked whether people around the world would be better or worse off in the future. Only 17% of those who got no correct answers on historical development changes thought the world would be better off. 62% of those with more than five correct answers did.

Started working at Gayes foundation and their motto is Optimists on a mission. It is easier when there are resources and influence to do something. There are too many things that seem impossible to change and culture and politics that seem to inevitably directed to make the future worse and not better.

Optimism needs community and purpose to feed it and keep it alive.

SUPERB (AND TIMELY…) PIECE!!!

PS: The reason most news about the world is negative is not that bad events occur rapidly while good ones progress slowly (a dubious claim in its own right, imho). Rather, it lies in the media’s focus on processing bad news to cater to our ancestral hunger for threat signals. This predisposition was extremely advantageous when we lived in caves, facing constant and sudden survival risks; our hypothalamus and amygdala remain tuned to that environment.