Are bees booming or dying off?

Bees are more than just honeybees.

Some of you might have seen a post online that goes like this:

“The media has told you that the bees are dying. But look at this chart: there are more bees than ever!”

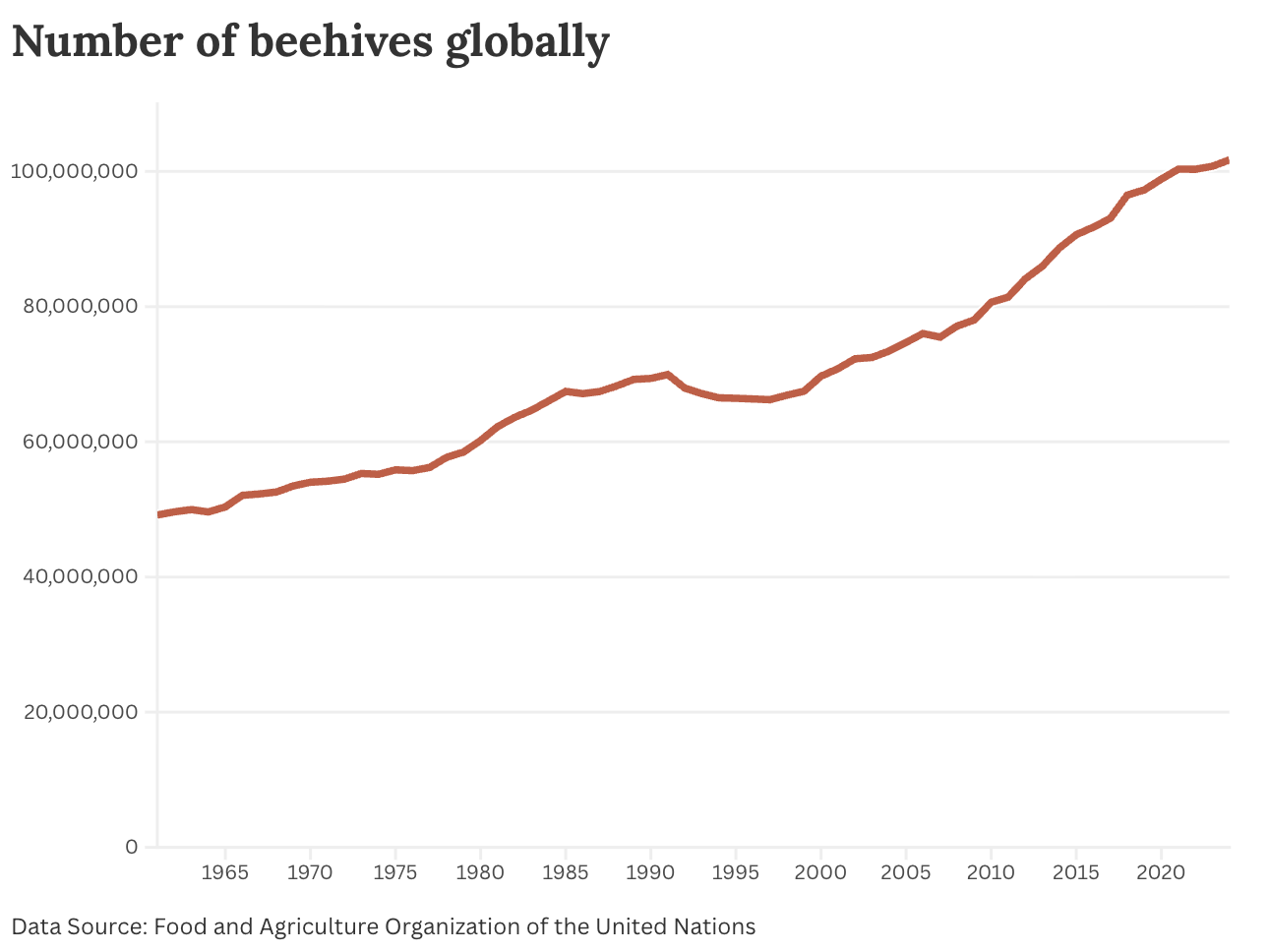

They’ll then show a chart like this:

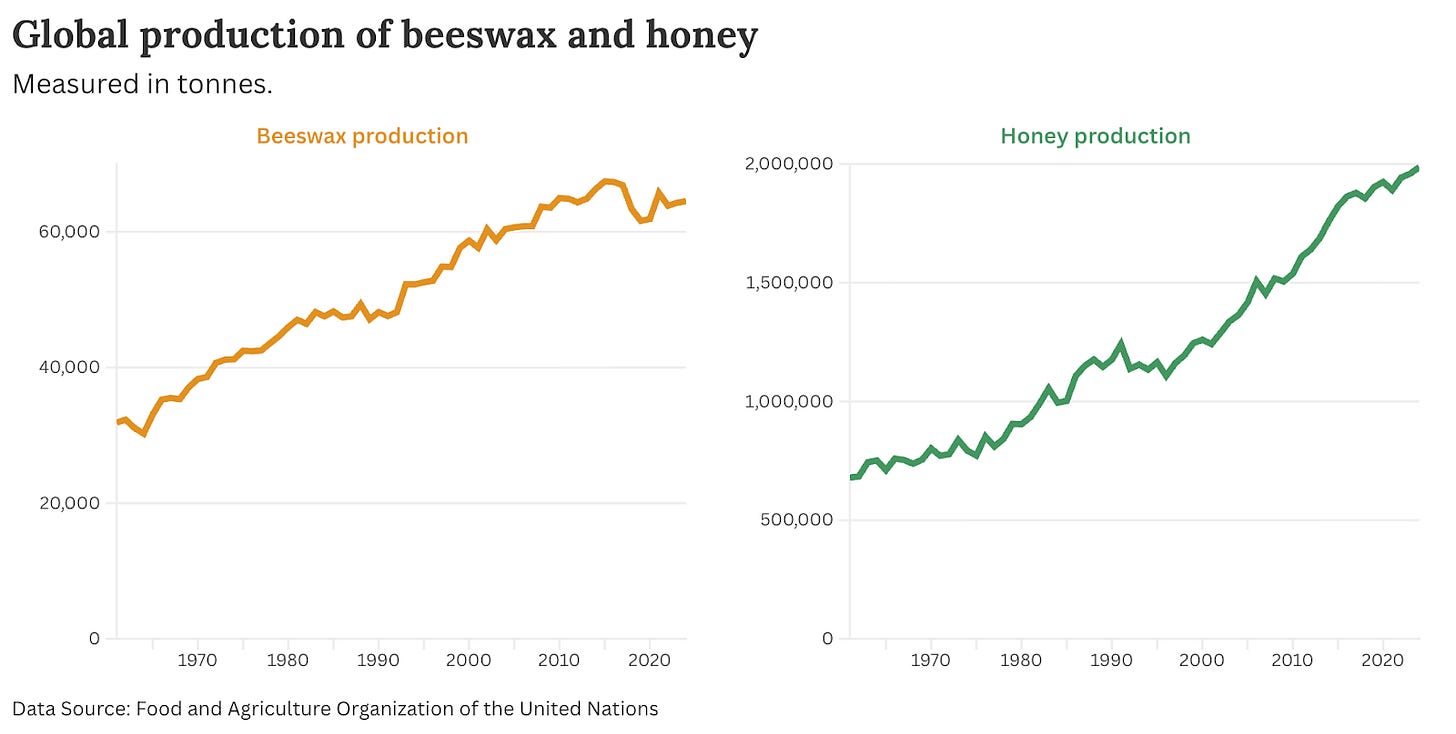

Or similar data showing the global production of honey and beeswax:

Now, there’s nothing wrong with this data. It is published by the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations. You’ll find similar data from the US Department of Agriculture (USDA).

But the interpretation of this data — and what it means for bee populations more broadly — is sometimes off.

What this data shows is the number of honeybees (or, in this case, beehives, which are often used as a proxy for individual bees) that are farmed to produce honey and beeswax.1 They are, essentially, livestock.

It’s true that managed honeybee populations are doing well overall.2 Hive numbers have risen over time, and global honey production has increased too.

[Note that this is not true everywhere. There are fewer beehives in the United States than there were 50 years ago. I’ve plotted this data across selected regions here].

Yet every few years, there are headlines about honeybees in crisis somewhere in the world — sometimes even warning of a world without any bees. These concerns are often real. Honeybees do struggle: beekeepers can lose a large share of their colonies each year. But somehow the system muddles through. Colonies are replaced, production continues, and the headlines become fodder for people trying to dismiss concerns about insect decline.

But crucially, “bees” doesn’t just mean “honeybees”. A chart of honeybee populations — which is basically just one species, Apis mellifera — tells us nothing about how the thousands of wild bee species are doing.

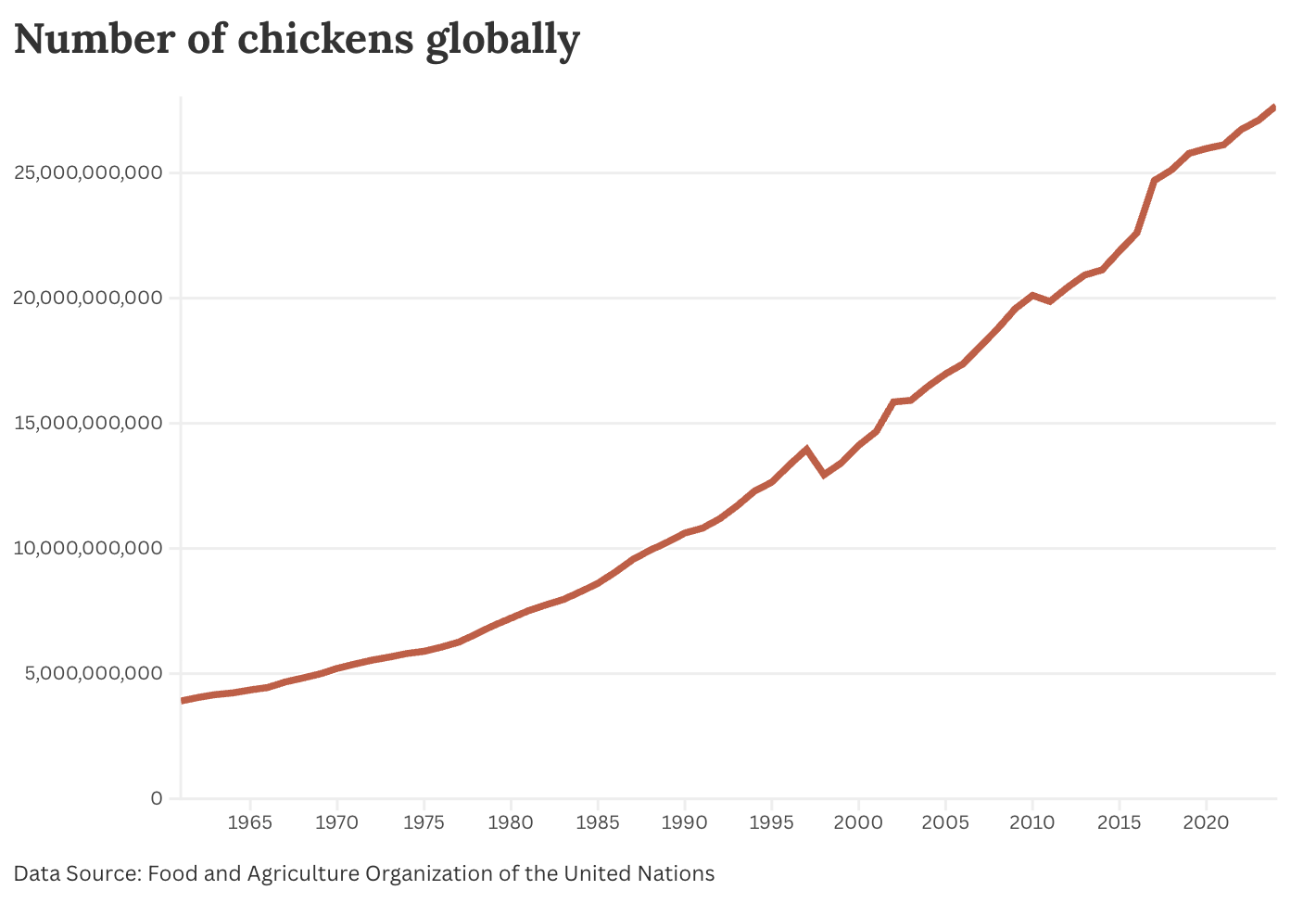

It would be like showing this chart of chickens (which are mostly factory-farmed) and saying, “People say that bird populations are struggling. But there are more chickens than ever!”

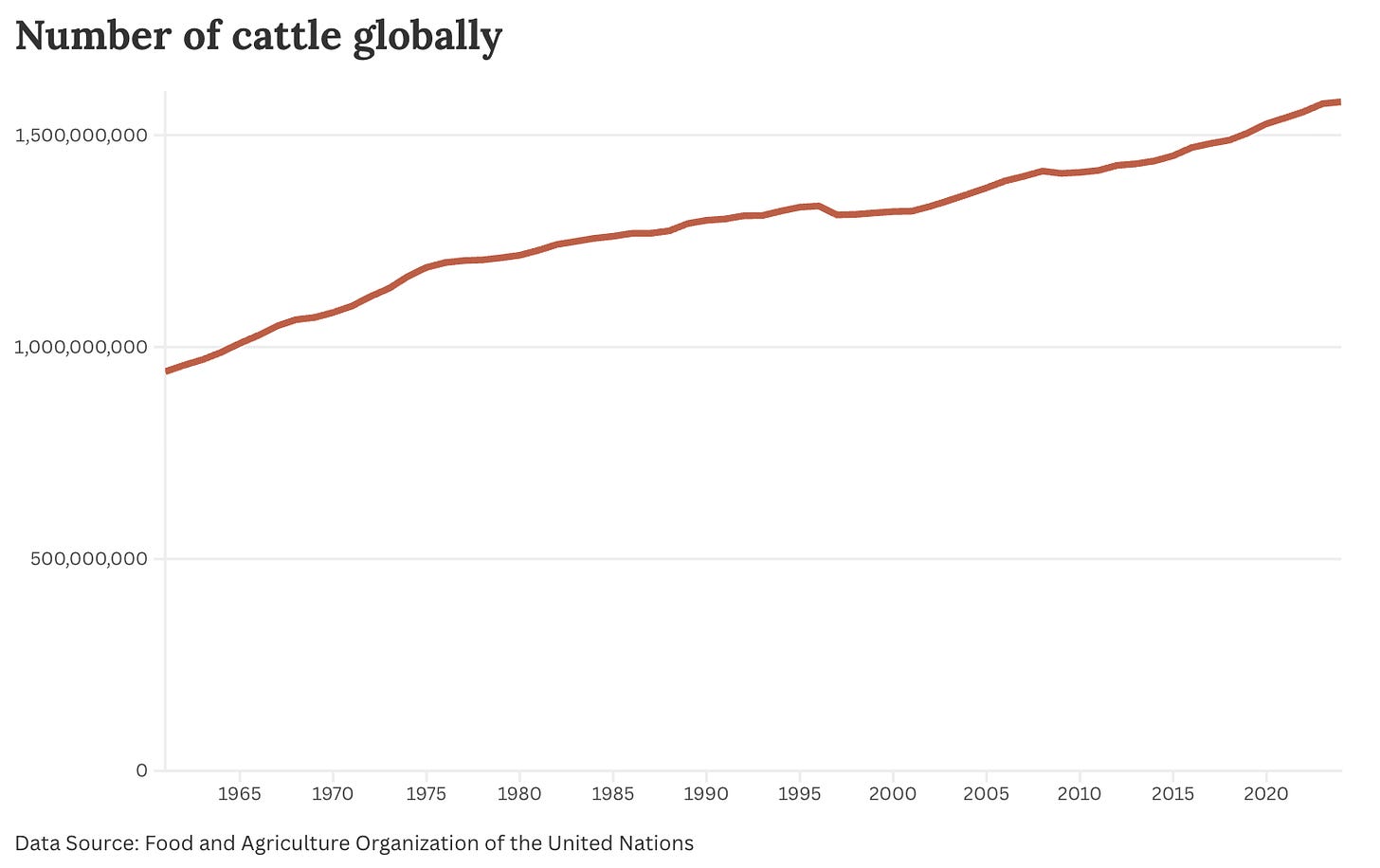

Or showing the number of farmed cows and concluding that global mammals are flourishing.3

If all we care about is food production, these metrics are useful. We’ve become extremely good at raising livestock at scale: producing feed, managing disease, and keeping populations productive.4

But again, the debates about the state of honey bee populations are completely disconnected from what’s happening to bumble and wild bee species. Just as conversations about cows or pigs are disconnected from ones about elephants or chimpanzees.

Why should we care about wild bees?

A couple of reasons. First, the intrinsic one: if you care about protecting a wide range of species on the planet, you might care about maintaining more than one species of bee. Second, the practical one: wild bees often pollinate different plants (and some crops). Wild bees can also be more effective pollinators. For many crops and wild plants, they deliver more pollination per visit than honeybees.

Wild bee populations are not doing so well. Global data is much poorer than the data we have on managed honeybees. But from the available evidence, I think it’s reasonable to conclude that they’re in decline. Not “insectageddon” level declines (again, overblown narratives on this make it easier for people to discredit valid concerns about biodiversity loss). But many species have seen a shrinking of range, population reductions, and are creeping up the rungs of extinction risk.

A range of local and regional studies find negative trends.5 And while global studies are rare, one major analysis using records in the Global Biodiversity Information Facility found that the number of wild bee species recorded each year has fallen by around 25% since the 1990s — even as the total number of records increased.6

Crucially, one of the threats to wild bee species is the presence of honeybees themselves.7 Since the latter are effectively managed populations, they can be introduced to an ecosystem in much higher densities. These honeybees introduce competition for nectar and pollen, and can also spread pathogens and parasites via shared flowers and hive movements.8 In many places, the honeybee is a non-native species competing with native ones for resources.

So, the chart of honeybees doing well might actually mean the opposite for other bee species.

To be clear: this isn’t about “good bees” and “bad bees”. Honeybees and wild bees both matter. But when you see claims about flourishing bee populations or rallying cries to “Save the bees”, it’s worth pausing and questioning what bees they’re talking about.

The size of bee colonies can vary, so using the number of colonies to estimate the number of bees is just a rough proxy.

This is also reflected in the scientific literature:

Phiri, B. J., Fèvre, D., & Hidano, A. (2022). Uptrend in global managed honey bee colonies and production based on a six-decade viewpoint, 1961–2017. Scientific reports, 12(1), 21298.

It’s true that global mammal biomass has been increasing — quite dramatically — over the last few centuries. That’s mostly due to humans and livestock, which now dominate.

Wild mammals have declined, though, and now make up only a few percent of the total. We wrote about this here: https://ourworldindata.org/wild-mammals-birds-biomass

For us as humans, in terms of product outputs. Not in terms of animal welfare, which has often gone in the opposite direction to make farms more productive.

Studies have a very strong bias towards North America and Europe, with far fewer studies across Asia, Africa, and South America.

Powney, G. D., Carvell, C., Edwards, M., Morris, R. K., Roy, H. E., Woodcock, B. A., & Isaac, N. J. (2019). Widespread losses of pollinating insects in Britain. Nature communications, 10(1), 1018.

Koh, I., Lonsdorf, E. V., Williams, N. M., Brittain, C., Isaacs, R., Gibbs, J., & Ricketts, T. H. (2016). Modeling the status, trends, and impacts of wild bee abundance in the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(1), 140-145.

Cameron, S. A., Lozier, J. D., Strange, J. P., Koch, J. B., Cordes, N., Solter, L. F., & Griswold, T. L. (2011). Patterns of widespread decline in North American bumble bees. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(2), 662-667.

The authors report an approximately 25% decline in the period from 2006 to 2015, relative to the 1990s.

Zattara, E. E., & Aizen, M. A. (2021). Worldwide occurrence records suggest a global decline in bee species richness. One Earth, 4(1), 114-123.

Iwasaki, J. M., & Hogendoorn, K. (2022). Mounting evidence that managed and introduced bees have negative impacts on wild bees: an updated review. Current Research in Insect Science, 2, 100043.

MacInnis, G., Normandin, E., & Ziter, C. D. (2023). Decline in wild bee species richness associated with honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) abundance in an urban ecosystem. PeerJ, 11, e14699.

Travis, D. J., Kohn, J. R., Holway, D. A., & Hung, K. L. J. (2025). Pollen exploitation by non‐native, feral honey bees: Potential consequences for interspecific competition. Insect Conservation and Diversity, 18(6), 1109-1119.

Davis, T. S., Mola, J., & Comai, N. (2025). Honeybee presence restructures pollination networks more than landscape context by reducing foraging breadths of wild bees. Landscape and Urban Planning, 257, 105305.

As always thank you for your work. When you have a moment, can you address the anti-environment claims of the otherwise fine Landman? My only experience with insect armageddon is driving from montreal to boston in 1970s and 80s and having to stop 2 or 3 times to wipe windshield. Now i can drive 1000 miles with nary an insect gut to be found. I wondered if theyve designed better windshields but it’s not that. What do the data show?

Since we've ditched the lawn and put our yard into natives plants I've been amazed at the variety of bees and insects in general that we see now. Yes, a few are mildly problematic but manageable. It's really opened my eyes to how many different bees there are out there that suburbs and farm fields don't seem to support.